Becoming Gesar, the fearless Buddhist: How to overcome fear in uncertain times, according to Pali Sutta, Mahayana Sutra and Tantra

Buddha Weekly: Buddhist Practices, Mindfulness, Meditation. Copyright Buddha Weekly.

Gesar of Ling was a fearless Buddhist king of 1027A.D. His story teaches, in allegory, how to overcome fear, and how to destroy our maras (especially fear). [More on King Gesar below.]

Fear is a necessary survival instinct, and — as long as we cling to this precious, human life — it is often what keeps us safe from harm. It can also be debilitating to the point of making us feel sick. Fear is mentioned prominently in all of Buddha’s cycles of teaching: Pali Sutta, Mahayana Sutra and Tantra — usually as a hurdle or defilement.

Buddha taught us how to overcome our fears in different ways in the Three Vehicles of Buddhism.

Even in our “regular” lives, Fear is an obstacle in times of heightened anxiety: times of political instability, war, terrorism, chronic unemployment, recession, or, an outbreak of a disease (such as SARS). Then, fear becomes a dangerous stress-factor, debilitating and seemingly insurmountable.

The allegorical Buddhist epic of 1 million verses, Gesar of Ling, demonstrates how we can overcome our fears and obstacles with courage in the Dharma.

The remedy according to Pali Sutta, Mahayana Sutra and Tantra

The most often cited “remedies” for fear are as varied as the teachings of the Buddha:

- In Pali Sutta, such as Abhaya Sutta, Buddha teaches us we will have no fear if we attain “certainty with regard to the True Dhamma” and teaches us four types of people who do not feel fear — and how we can be like them (see Abhaya Sutta, below).

- In Mahayana Sutra — such as Heart Sutra — we take refuge in the Three Jewels as protection. We are also taught that our own Buddha Nature gives us no reason to fear. We practice Compassion (Metta) — by caring for others as much as our selves, we feel protective and strong, rather than afraid. (The Dharma Bodhisattva, or the Hero, like King Gesar of LIng.)

- In Tantra, the visualized meditative path, in addition to the Pali Sutta and Mahayana Sutras, we also visualize and work with the Buddhas and Yidams who represent protection: such as Green Tara, Palden Lhamo, Black Mahakala and other protectors — in other words, our connection to our higher Buddha Natures.

Buddha often spoke about “fear” in the suttas (sutras), and most notably in the Abhaya Sutta [Fearless Sutta: full English translation appended to this feature]. It is not by accident that sutta (sutra) translators often now tend to translate “dukka” as “stress” rather than the older interpretations “suffering.” For instance, Thanissaro Bhikku, who has translated countless Pali Suttas, translates Calu-dukkha-khandha Sutta as “The Less Mass of Stress.” It is this stress that Buddha taught us to overcome.

The Five Fears — and our addiction to fear

Buddha named five fears, which certainly we can all relate to:

- Fear of death

- Fear of illness

- Fear of losing our mind and memories (today, a big fear, for example, is Dementia)

- Fear of losing our livelihood (our jobs)

- Fear of public speaking.

Today, in modern society, there are more fears than ever, yet the timeless teachings of the Buddha help us overcome debilitating fear.

Equally problematic is our addiction to fear. We feed it with our need to read the “bad news” in the media every day, and we spread manure on it with unrestrained social media. We fan the flames of fear by watching horror movies. We try to avoid fear, but at the same time, we’re addicted to it — as with all things in Samsaric life.

Concise fear advice: the Dhammapada

As always, Buddha gave us both concise advice and more elaborate teachings. The go-to for concise advice, the Dhammapada (collection of sayings of the Buddha 212-216) certainly has powerful teachings on fear:

From what is dear, grief is born,

from what is dear, fear is born.

For someone freed from what is dear

there is no grief

— so why fear?From what is loved, grief is born,

from what is loved, fear is born.

For someone freed from what is loved,

there is no grief

— so why fear?From delight, grief is born,

from delight, fear is born.

For someone freed from delight

there is no grief

— so why fear?From sensuality, grief is born,

from sensuality, fear is born.

For someone freed from sensuality

there is no grief

— so why fear?From craving, grief is born,

from craving, fear is born.

For someone freed from craving

there is no grief

— so why fear?

Buddha teaching.

Stress is the Disease; Dharma is the Cure

Buddhist meditation, so well accepted in the west (particularly, mindfulness) is famous for reducing “stress” — so the metaphor of “stress is the disease, Dharma the cure, Buddha the doctor” — seems very modern and appropriate. In fact, Dukkha can be translated a dozen ways, depending on context: painful experience, anxiety, conditioned experience, sorrow, pain, despair. It also literally translates as “uneasy” or “unpleasant” or “causing of pain.” The word stress applies, in a way, to all of these — the outcome of our pain, despair, sorrow and anxiety is stress.

We are stressed when we fear for our lives because of the latest terror attack, or threat of nuclear attack.We are stressed when we can’t afford what we want. We are stressed when we are infatuated with a beautiful person we can never possess.

Shakyamuni subdues an elephant with loving kindness and the Abhaya gesture. The elephant was enraged by evil Devadatta.

Stress is the disease that Buddha — often metaphorically described as “the Doctor” — is treating. It is our clinging to our possessions, our need to have even better “things,” our clinging to our youth, that causes stress and fear when we think of losing them. So, who is it who doesn’t feel fear? Buddha described, in the Abhaya Sutta, four types of people that do not feel fear, notable among them, the person who understands the True Dharma:

“Furthermore, there is the case of the person who has no doubt or perplexity, who has arrived at certainty with regard to the True Dhamma. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought occurs to him, ‘I have no doubt or perplexity. I have arrived at certainty with regard to the True Dhamma.’ He does not grieve, is not tormented; does not weep, beat his breast, or grow delirious. This, too, is a person who, subject to death, is not afraid or in terror of death.”These, Brahman, are four people who, subject to death, are not afraid or in terror of death.”

Heart Sutra: and the “Great Mantra”

In Mahayana teachings, The Heart Sutra, almost certainly the most beloved of Sutras, goes to the heart (pun intended) of the remedy:

In Mahayana teachings, The Heart Sutra, almost certainly the most beloved of Sutras, goes to the heart (pun intended) of the remedy:

With no hindrance in the mind.

No hindrance, therefore no fear.

Far beyond deluded thoughts, this is Nirvana.

Among the shortest and most beautiful of all Sutras, the Heart Sutra is also one of the most difficult. It has many layers of meaning and nuances. Heart Sutra is a lifetime meditation for many Buddhists, and also contains among the most powerful of mantras for protection from fear:

“Bodhisattvas who practice

the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore

see no more obstacles in their mind,

and because there

are no more obstacles in their mind,

they can overcome all fear,

destroy all wrong perceptions

and realize Perfect Nirvana……Therefore Sariputra,

it should be known that

the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore

is a Great Mantra,

the most illuminating mantra,

the highest mantra,

a mantra beyond compare,

the True Wisdom that has the power

to put an end to all kinds of suffering.

Therefore let us proclaim

a mantra to praise

the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore.Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha!

Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha!

Gate, Gate, Paragate, Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha!” [1]

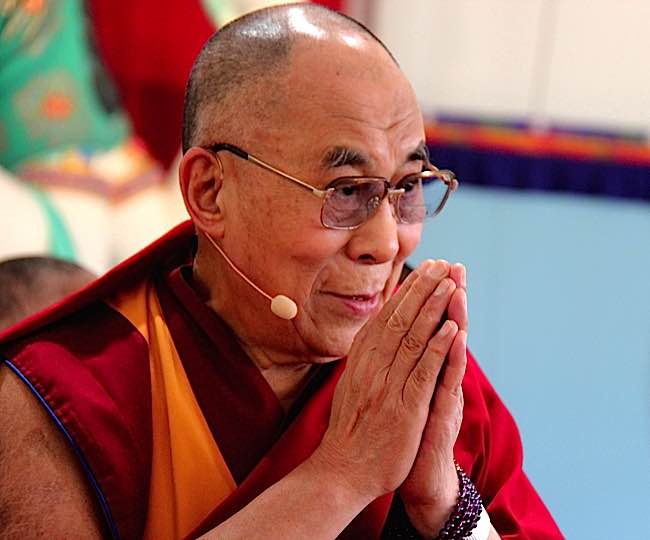

His Holiness, the Dalai Lama’s advice

The Dalai Lama has advice for fear in our times.

The Dalai Lama has spoken of fear many times. In “A Policy of Kindness,” he summarized a few principles for handling fear:

“…someone who is engaging in the Bodhisattva practices seeks to take others’ suffering onto himself or herself. When you have fear, you can think, “Others have fear similar to this; may I take to myself all of their fears.” Even though you are opening yourself to greater suffering, taking greater suffering to yourself, your fear lessens.”

He also wrote: “Another technique is to investigate who is becoming afraid. Examine the nature of your self. Where is this I? Who is I? What is the nature of I? Is there an I besides my physical body and my consciousness? This may help.” This get’s to the heart of the Heart Sutra (again, pun intended.)

Lankavatara Sutra: Buddha Nature

Many Mahayana Sutras give “remedies” for fear. In Lankavatara Sutra, Buddha speaks elaborately about Buddha Nature — how we all have inherent Buddha Nature — and explains how to “cast aside fear”:

“The reason why the ‘Tathagatas’ who are Arhats and fully enlightened Ones teach the doctrine pointing to the tathagatagarbha (Buddha Nature) which is a state of non-discrimination and image-less, is to make the ignorant cast aside their fear when they listen to teaching of egolessness.”

Buddha Nature basically informs us that we all have Buddha within, obscured by our ignorance, obstacles and fears. We meditate to settle our obstacles and fears and to find the inner nature.

Tathagatagarbha (the doctrine of Buddha Nature) basically states (as quoted from the Third Karmapa):

“All beings are Buddhas,

But obscured by incidental stains.

When these have been removed,

There is Buddhahood.”

Often the metaphor of the sun behind the clouds is used. The clouds — our fears, uncertainties and defilements — obscure our true nature, Buddha Nature, the sun. Once the defilements of ego are removed, and there is an understanding of Shunyata (Emptiness, or Oneness), we are Buddha; there can be no more fear.

For a video teaching on Buddha Nature see>>

For a feature on Buddha Nature see>>

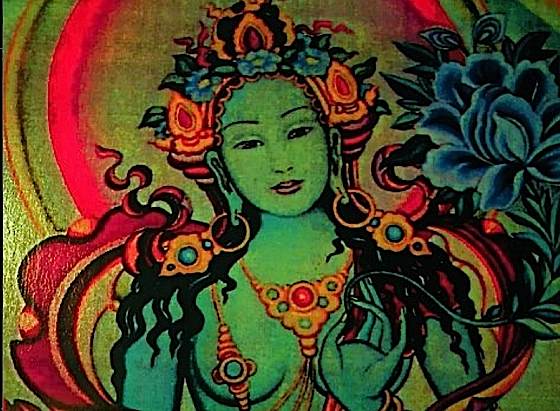

Tantra: Green Tara, the Protectress

Green Tara is one of the most popular Enlightened deity emanations in Mahayana Buddhism, and Her practice is the go-to for fear. Tibetans in trouble almost invariably (and almost involuntarily) chant the Tara mantra whenever there is danger or fear:

Om Tare Tuttare Ture Svaha

Pronounced: Ohm Tah-ray Tew-tah-ray Tew-ray Svah Ha

Or Tibetan: Om Tare Tuttare Ture Soha

Tara represents the “activity” of the Buddhas, the windy power that protects her children. She is revered by millions of Buddhists.

Tara is the aspect or emanation of Buddha who is the protective mother — as fierce as the mother Grizzly bear protecting us, her cubs. There are numerous stories of Tara’s miraculous interventions. [For some stories of her famous rescues, see this feature>>]

Tara in the Palm of Your Hand, teaches how to overcome fear through Tara practice. A book by Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche, available on Amazon>>

For instance, H.E. Zasep Rinpoche [2] told the story of the collapsing balcony:

“I had parked my car, which had a picture of Tara in it, next to an apartment building. While I was away doing an errand, a concrete balcony on the building collapsed, crushing the two cars next to mine, but leaving mine intact, albeit dusty.”

Is Tara a self-aware deity who swoops down to save us? No, Buddhas are beyond self-aware ego. Bokar Rinpoche explains: “In truth, if we realize the true nature of our minds, the deities reveal themselves as being not different from our own minds.”[3] He also helps us understand how Tara helps, explaining it in the terms of Buddha Nature (we all have Buddha Nature, and at that level we’re all connected):

This isn’t a “green goddess sweeping down” but often takes the form of listening to our own intuitive mind (wisdom). There’s also an element of Karma in these stories. By relying on Tara, this itself is meritorious karma, making our outcomes in life more positive.

For a full feature story on Green Tara, see:

Tonglen Practice: giving and taking

The Buddhist Warrior: Gesar of Ling

King Gesar of Ling, the fearless Dharma king. His adventures told in a million verses, are a story of Dharma conquering the maras (evils or obstructions.)

In Tibet, Mongolia, Nepal and many parts of Asia, people grew with stories of the epic of Gesar of Ling. Inspiration from these stories can help overcome fears.

New beautiful hardcover boxed book, The Epic of Gesar of Ling: Gesar’s Magical Birth, Early Years and Coronation as King, from Shambala.

“When we talk here about conquering the enemy, it is important to understand that we are not talking about aggression. … Thus the idea of warriorship altogether is that by facing all our enemies fearlessly, with gentleness and intelligence, we can develop ourselves and thereby attain self-realization.” [4]

Gesar of Ling statue.

Abhaya Sutta

Fearless

Translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Then Janussoni the Brahman went to the Blessed One and, on arrival, exchanged courteous greetings with him. After an exchange of friendly greetings and courtesies, he sat to one side. As he was sitting there he said to the Blessed One: “I am of the view and opinion that there is no one who, subject to death, is not afraid or in terror of death.”

The Blessed One said: “Brahman, there are those who, subject to death, are afraid and in terror of death. And there are those who, subject to death, are not afraid or in terror of death.

“And who is the person who, subject to death, is afraid and in terror of death? There is the case of the person who has not abandoned passion, desire, fondness, thirst, fever, and craving for sensuality. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought occurs to him, ‘O, those beloved sensual pleasures will be taken from me, and I will be taken from them!’ He grieves and is tormented, weeps, beats his breast, and grows delirious. This is a person who, subject to death, is afraid and in terror of death.

“Furthermore, there is the case of the person who has not abandoned passion, desire, fondness, thirst, fever, and craving for the body. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought occurs to him, ‘O, my beloved body will be taken from me, and I will be taken from my body!’ He grieves and is tormented, weeps, beats his breast, and grows delirious. This, too, is a person who, subject to death, is afraid and in terror of death.

“Furthermore, there is the case of the person who has not done what is good, has not done what is skillful, has not given protection to those in fear, and instead has done what is evil, savage, and cruel. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought occurs to him, ‘I have not done what is good, have not done what is skillful, have not given protection to those in fear, and instead have done what is evil, savage, and cruel. To the extent that there is a destination for those who have not done what is good, have not done what is skillful, have not given protection to those in fear, and instead have done what is evil, savage, and cruel, that’s where I’m headed after death.’ He grieves and is tormented, weeps, beats his breast, and grows delirious. This, too, is a person who, subject to death, is afraid and in terror of death.

“Furthermore, there is the case of the person in doubt and perplexity, who has not arrived at certainty with regard to the True Dhamma. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought occurs to him, ‘How doubtful and perplexed I am! I have not arrived at any certainty with regard to the True Dhamma!’ He grieves and is tormented, weeps, beats his breast, and grows delirious. This, too, is a person who, subject to death, is afraid and in terror of death.

“These, Brahman, are four people who, subject to death, are afraid and in terror of death.

“And who is the person who, subject to death, is not afraid or in terror of death?

“There is the case of the person who has abandoned passion, desire, fondness, thirst, fever, and craving for sensuality. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought does not occur to him, ‘O, those beloved sensual pleasures will be taken from me, and I will be taken from them!’ He does not grieve, is not tormented; does not weep, beat his breast, or grow delirious. This is a person who, subject to death, is not afraid or in terror of death.

“Furthermore, there is the case of the person who has abandoned passion, desire, fondness, thirst, fever, and craving for the body. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought does not occur to him, ‘O, my beloved body will be taken from me, and I will be taken from my body!’ He does not grieve, is not tormented; does not weep, beat his breast, or grow delirious. This, too, is a person who, subject to death, is not afraid or in terror of death.

“Furthermore, there is the case of the person who has done what is good, has done what is skillful, has given protection to those in fear, and has not done what is evil, savage, or cruel. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought occurs to him, ‘I have done what is good, have done what is skillful, have given protection to those in fear, and I have not done what is evil, savage, or cruel. To the extent that there is a destination for those who have done what is good, what is skillful, have given protection to those in fear, and have not done what is evil, savage, or cruel, that’s where I’m headed after death.’ He does not grieve, is not tormented; does not weep, beat his breast, or grow delirious. This, too, is a person who, subject to death, is not afraid or in terror of death.

“Furthermore, there is the case of the person who has no doubt or perplexity, who has arrived at certainty with regard to the True Dhamma. Then he comes down with a serious disease. As he comes down with a serious disease, the thought occurs to him, ‘I have no doubt or perplexity. I have arrived at certainty with regard to the True Dhamma.’ He does not grieve, is not tormented; does not weep, beat his breast, or grow delirious. This, too, is a person who, subject to death, is not afraid or in terror of death.

“These, Brahman, are four people who, subject to death, are not afraid or in terror of death.”

When this was said, Janussoni the Brahman said to the Blessed One: “Magnificent, Master Gotama! Magnificent! Just as if he were to place upright what was overturned, to reveal what was hidden, to show the way to one who was lost, or to carry a lamp into the dark so that those with eyes could see forms, in the same way has Master Gotama — through many lines of reasoning — made the Dhamma clear. I go to Master Gotama for refuge, to the Dhamma, and to the Sangha of monks. May Master Gotama remember me as a lay follower who has gone to him for refuge, from this day forward, for life.”

NOTES

[1] Heart Sutra translation from Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh.

[2] Tara in the Palm of Your Hand, by Zasep Rinpoche

[3] Tara, the Feminine Divine, Bokar Rinpoche

[4] Foreward to Alexandra David-Neel’s The Superhuman LIfe of Gesar of Ling.

The post Becoming Gesar, the fearless Buddhist: How to overcome fear in uncertain times, according to Pali Sutta, Mahayana Sutra and Tantra appeared first on Buddha Weekly: Buddhist Practices, Mindfulness, Meditation.

from Buddha Weekly: Buddhist Practices, Mindfulness, Meditation https://ift.tt/2THGnhb

Post a Comment