Bodhidharma – The Legendary Founder of Zen Buddhism: “Who stands before me?” — “I don’t know.”

Buddha Weekly: Buddhist Practices, Mindfulness, Meditation. Copyright Buddha Weekly.

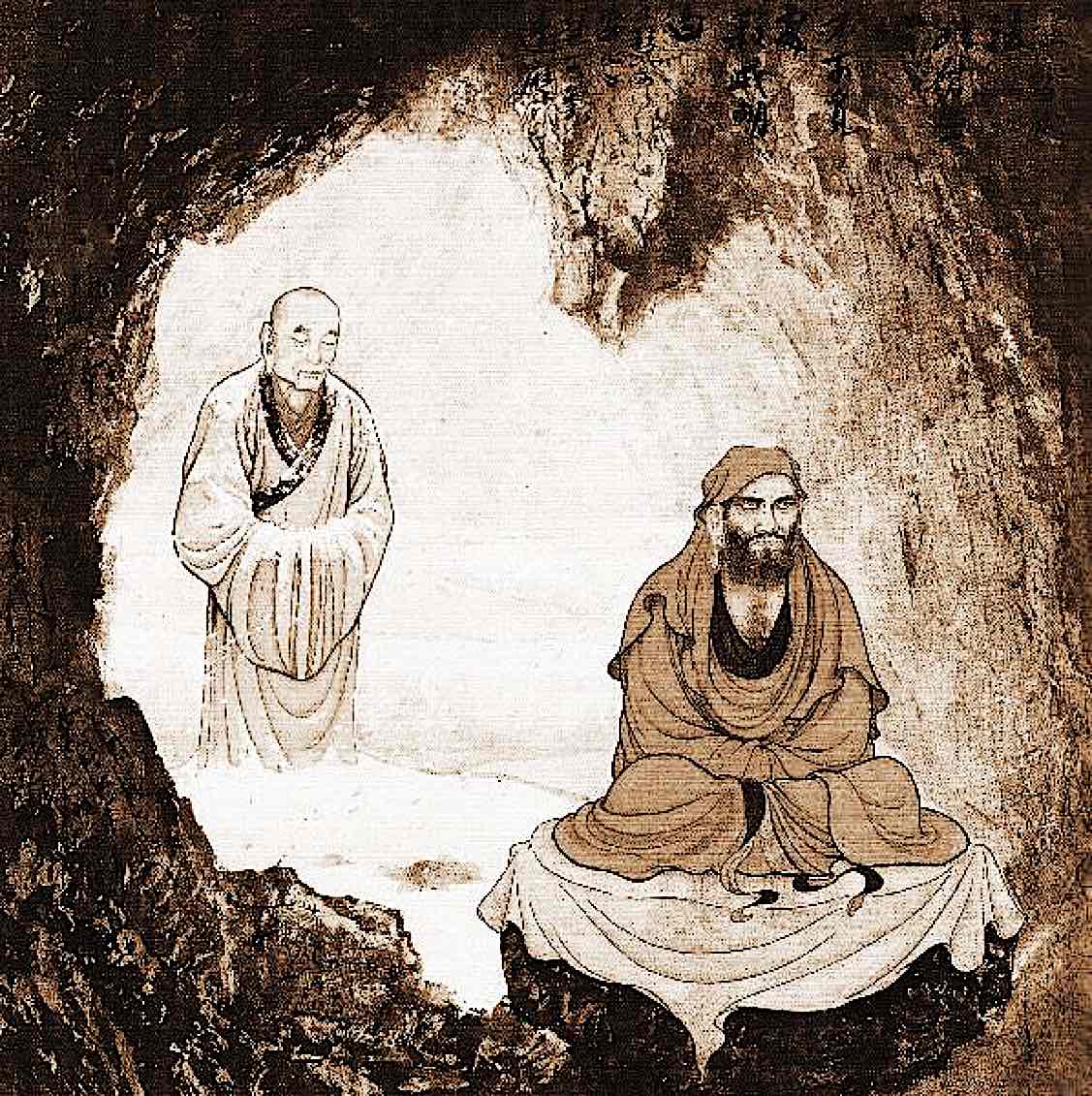

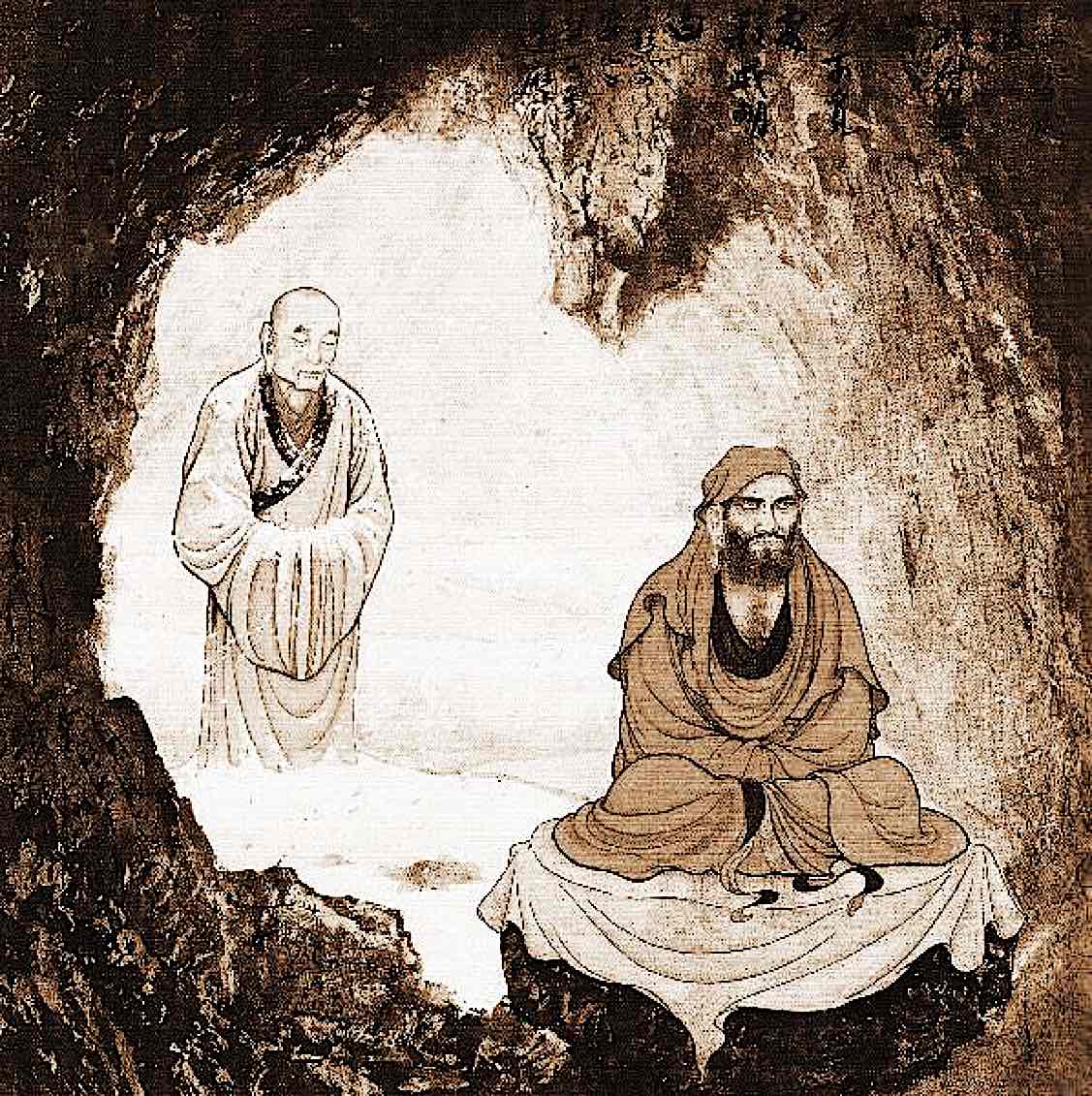

Bodhidharma meditating in a cave.

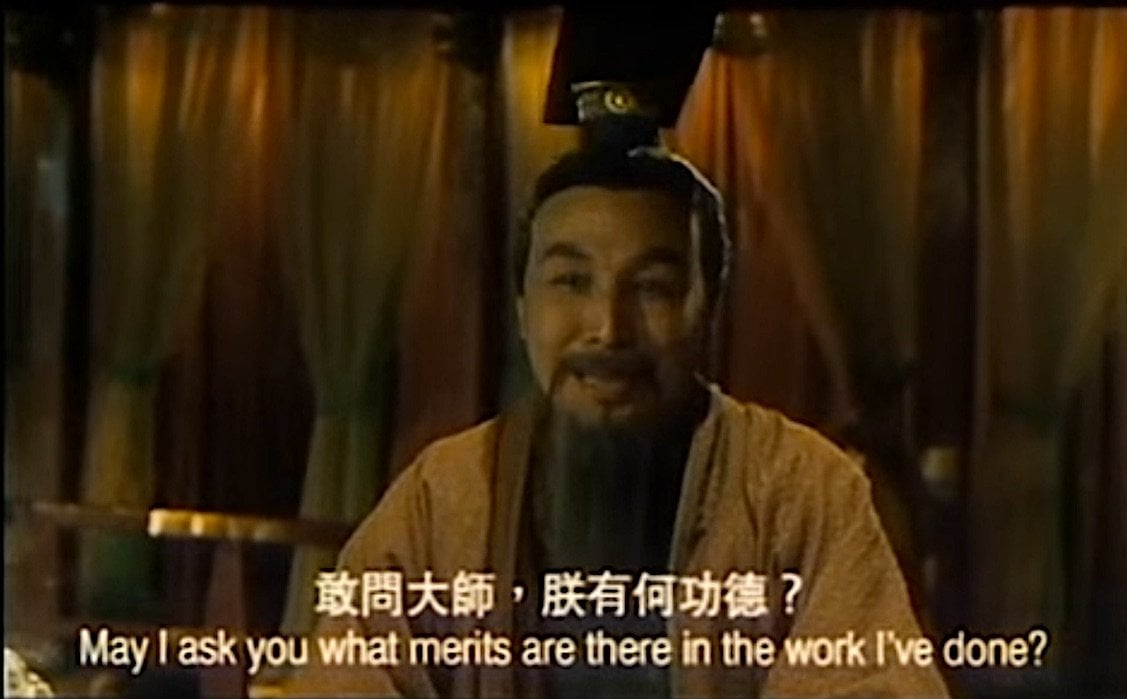

When Emperor Wu of Ryo of China, who was a patron of Buddhism, heard of the legendary monk Bodhidharma, he invited him to his court, expecting to receive teachings and wisdom. When they finally met, the emperor asked:

“What is the ultimate meaning of the holy truths of Buddhism?”

“Vast emptiness, no holiness,” replied Bodhidharma.

“Who stands here before me?” asked Emperor Wu.

“I don’t know” said Bodhidharma.

The Emperor was baffled. This story would come to define the legendary Patriarch Bodhidharma, who brought Ch’an Buddhism to China from India – and created a revolution in Buddhist thinking that remains influential today. (See the legendary account of Bodhidharma in the movie embedded below (low resolution, unfortunately.)

Emperor of China asks Bodhidharma who it is before him. Bodhidharma says, “I don’t know” From a Chinese movie The Master of Zen — the life of Bodhidharma. (Full movie embedded below.)

Bodhidharma, shrouded in mystery

Bodhidharma’s life is shrouded in mystery — famous for bringing Chan or Zen Buddhism from India to China. He lived in the fifth or sixth century C.E. Said to have been born into a privileged, upper-class life in South India, he left his homeland to spread his teaching in China, and his exploits there became the stuff of legend. He helped shape Buddhism not only in China but also Japan, Vietnam, Korea and ultimately, around the world.

As with all great and mysterious people, accounts of Bodhidharma’s life developed mythic elements. Scholars, historians and Zen Buddhists have pieced together his story through various sources — without the legendary symbolism. Much of what we know about Bodhiharma is also expressed in Zen Koans and riddles that mention him. [For a feature on Zen Koans, see>>]

The movie version of Bodhidharma’s life — which does include some “mythic” elements of the story and is, of course, fictionalised (the above exchange with the Emperor is found around 42 minutes in.):

C’han / Zen and Bodhidharma

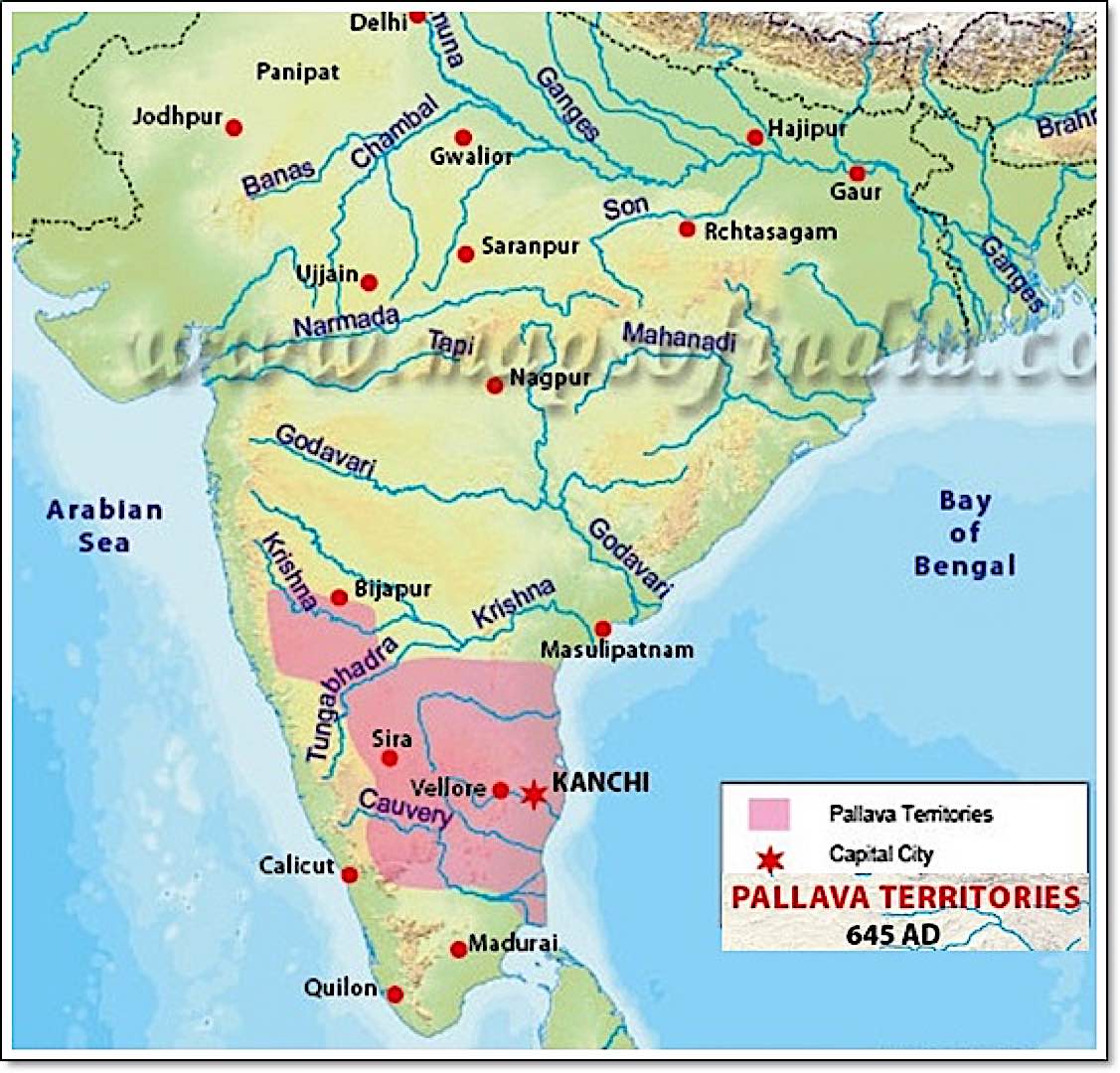

Where Bodhidharma may have been born and raised.

Bodhidharma brought a new type of Buddhism which became known in China as Ch’an. Ch’an simply means “meditation. The school was unique in the fact that it put direct experience above the reading and chanting of scriptures. He realised that the Buddha had become enlightened by direct perception of the truth of enlightenment, not by reading scriptures or making grand intellectual theories and he sought to replicate this. Bodhidharma is said to have defined Ch’an’s ethos as follows which remains one of the best definitions of it to this day:

“A special transmission outside the scriptures, No basis in words or writing. Direct pointing to the mind of people. Insight into one’s nature and attainment of Buddhahood.” [1]

This tends to make people think that Ch’an/Zen rejects the Buddhist scriptures and it has also been labelled anti-intellectual by some Westerners. Bodhidharma, as well as Zen more generally, does not reject the Buddhist scriptures, it merely shifts the focus from them to direct experience, it regards them as a guide to, rather than the full expression of Buddhist teaching. Ironically, Zen has produced a rich textual and doctrinal tradition independently of other schools which include Koans and the recorded sayings of masters and patriarchs. Some masters such as Hakuin Ekaku said that one must start with intellectual study.

One classic example of “going beyond” intellect was this famous exchange between Bodhidharma and his disciple Huike:

Huike said to Bodhidharma, “My mind is anxious. Please pacify it.”

Bodhidharma replied, “Bring me your mind, and I will pacify it.”

Huike said, “Although I’ve sought it, I cannot find it.”

“There,” Bodhidharma replied, “I have pacified your mind.”

Bodhidharma comforts his disciple Huiku. From the movie The Master of Zen.

A three-year journey to China

Bodhidharma’s journey across to China was said to have taken three years. Once there he was not welcomed and faced much opposition for his non-traditional views. Most Chinese Buddhism, at that time, was based on sutras and traditions. Meanwhile, this man from India, this Bodhidharma, claimed scriptures weren’t very important.

Bodhidharma, like Buddha before him, appeared to be a radical. They must have thought, something like: if you have no scriptural foundation for your school, where was your legitimacy? Bodhidharma’s teachings became a pardigm shift in Buddhist history — teaching that silence and experiential mediation — rather than just reciting sutras — could be the secret to great insights.

Bodhidharma travelling. He travelled for three years from India to China.

Famous humor and terseness

One of the main aspects of Bodhidharma is his sense of humor. Many great teachers through the ages have exhibited great warmth and humor. His way of teaching included “shaking up the mind” and shocking his audience, not just for the sake of leaving the student chuckling — but rather, to provoke deep thought. This humor is the basis for some of the most legendary and well known stories associated with him, two of them are about his encounter with Emperor Wu of Ryo who was a patron of Buddhism. The most famous is the one mentioned at the start of this piece.

The encounter with Emperor Wu described above became iconic of Bodhidharma’s terse – and, at times, quite funny – style of teaching. Almost like “Koans” — Zen riddles — he shook up the Emperor’s mind to help him develop his own insights. As Gerry Shishin Wick says, not only is Bodhidharma’s answer referencing the doctrine of no-self or ‘Anatta’ but it also means the following:

We believe that we are the content of our thoughts (and our opinions, beliefs, feelings and reactions). We resist seeing that we ourselves are “vast emptiness” and thus are denying our deep unlimited nature. The Buddha realised that there is no gap between ourselves and others. We are all one body. And by not recognising who we are, we are creating a chasm between ourselves and others that is greater than the Grand Canyon.[3]

When the Emperor of China asked Bodhidharma if his Dharma work had earned him any special merit, the sage answered “None Whatsoever.”

No merit whatsoever

In another famous story with the same Emperor, Wu told Bodhidharma that he had built many Buddhist temples and supported the Sangha, he was wondering how much positive karma he would receive from his actions. “None whatsoever” Bodhidharma was said to have replied, again infuriating the Emperor.

As became evident, this answer helped point out to the Emperor that he did it for self-gain — instead of the good of others.[4] These stories illustrate Bodhidharma’s conscise humourous style of teaching. Yes, Bodhidharma could be difficult, annoying and confusing — but at the same time he is considered one of the most intelligent and profound of teachers.

Bodhidharma may seem a little harsh or strange to the modern student — but this was his style of teaching. He pointed out the essential point — “pointing out” rather than telling. He’d encourage his student to dive in and puzzle it out for themselves, shattering their usual way of thinking.

In legend at least, Shaolin martial arts are said to have originated with Bodhidharma, who brought the methods from India as a way to condition the body.

Bodhidharma lives on in Zen

This style has continued into Zen tradition up to the present day. Koans and “pointing out” are methods of teaching. Direct master to student transmission remains very important.

Bodhidharma is Zen Buddhism’s 28th patriarch in a line of dharma transmission that stretches back to the Buddha. In the famous “Flower Sermon”, Buddha transmitted wisdom to his disciple Mahakasyapa simply by holding and twirling a flower. Without a word, Buddha expresses the ineffable nature Suchness. This teaching is regarded by many as the start of the Zen tradition.

Falling asleep for nine years

Bodhidharma is said to have cut off his eyebrows after he fell asleep facing a wall during meditation.

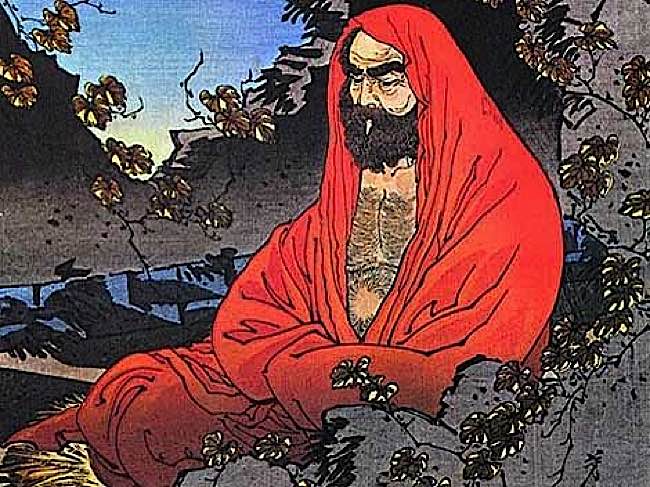

Among the more legendary stories of the great Zen patriarch, Bodhidharma is said to have fallen asleep whilst sitting in meditation, starring — for nine years. He was so irritated with himself, that he cut off his own eyelids in frustration. This is why in classical images of Bodhidharma, he is depicted with an intense stare.

He is also helped establish the Shaolin Monks’ training and prowess in martial arts and fighting styles, styles brought from India. These stories may be historical or mythical, but it just shows what the penetrating influence of Bodhidharma in Buddhism.

Influencial in many schools

Bodhidharma was influenced by a wide range of Buddhist thinking, by general Mahayana Buddhism, as well as the Indian Buddhist school known as Yogacara. That school had a focus on the mind and this can be seen in many aspects of Bodhidharma’s teaching. He taught that the concepts of enlightenment and even ‘Buddha’ were part of the mind, part of you and that you should see them as part of yourself. This is where some famous Koans such as “Kill the Buddha” arise from later on in the Zen tradition. Doing this, he taught would reveal the innate Buddha Nature of every person. Zen teaches that Buddha nature is not something to be gained from nothing, but realised as something that we had all along and that was hidden by our everyday mind. A quote attributed to him says:

“As long as you look for a Buddha somewhere else, you’ll never see that your own mind is the Buddha”.[6]

Bodhidharma’s death

We remain unsure about Bodhidharma’s death, some say he was killed by a jealous disciple in a cave, some say he decided the time was right to die, having spread his teaching successfully to China and allowed himself to die willingly in meditation. Some say he was killed in the Heyin Massacre of 528. No matter how he died, his death is just as strange as his life and this only increases the air of mystery around him.

Bodhidharma, the great chan sage.

A strange, profound legacy

The great patriarch of Ch’an Bodhidharma, who brought Zen’s precursor to China from India. Statue in the Shaolin temple Songshan Denfent City in Henan Province.

Bodhidharma leaves us with a strange, but profound legacy. Bodhidharma taught that direct perception were ultimately important than “words and scriptures” though, by no means, did he reject them.

After his death, Ch’an Buddhism spread throughout China merging with elements of the indigenous Taoist religion and from there spread to Vietnam where it became known as ‘Thein’, Korea as ‘Son’ and most famously, to Japan where it became known as ‘Zen’.

Zen spread to the West where it acquired many more adherents. The teaching of “The Blue-Eyed Barbarian” as — he was known to the Chinese of his time — had a monumental impact on Asia. The result is an incredibly rich and varied tradition. Bodhidharma, the simple monk with big blue eyes and an untidy, bushy beard, may not seem like much at first glance but he undoubtedly ranks among the most influential sages of humanity’s spiritual heritage.[7] [8]

Huike said to Bodhidharma, “My mind is anxious. Please pacify it.”

Bodhidharma replied, “Bring me your mind, and I will pacify it.”

Huike said, “Although I’ve sought it, I cannot find it.”

“There,” Bodhidharma replied, “I have pacified your mind.”NOTES

[1]Ninian Smart ‘The World’s Religions’ (Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge: Victoria, Australia 1989). P.122

[2]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zen_scriptures

[3]Gerry Shishin Wick ‘The Book of Equanimity: Illuminating Classic Zen Koans’ Wisdom (Publications, United States 2005). Pp. 13-14

[4]Matt Stefon ‘Bodhidharma’ at https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bodhidharma [Accessed 18th September 2018]

[5]Barbara O’Brien ‘Yogacara’ at https://www.thoughtco.com/yogacara-school-of-conscious-mind-450019 [Accessed 18th September 2018]

[6]Brainy Quote, ‘Bodhidharma Quotes’ at https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/bodhidharma_267277 [Accessed 18th September 2018]

[7]New World Encyclopedia ‘Bodhidharma’ at http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Bodhidharma [Accessed 18th September 2018]

[8]Zen Buddhism ‘Bodhidharma (5th Century) at http://www.zen-buddhism.net/famous-zen-masters/bodhidharma.html [Accessed 18th September 2018]

The post Bodhidharma – The Legendary Founder of Zen Buddhism: “Who stands before me?” — “I don’t know.” appeared first on Buddha Weekly: Buddhist Practices, Mindfulness, Meditation.

from Buddha Weekly: Buddhist Practices, Mindfulness, Meditation https://ift.tt/2OX1Xvm

Post a Comment